The evolutionary life history of Willows (Salix spp.) have been shaped by floods and the extremes found in riparian habitats. With about 12 species of native Willows in the Southeast, this old friend has a lot to teach us about the land and strength in adaptability.

In the upcoming Willow Pack Basket workshop with Tyler Lavenburg, our fingers will be bending willow like the tiny currents and streams that have shaped them. We’ll also be joining Luke Cannon for a Magnificent Tree Walk shortly after on November 6. In the excitement leading up to these workshops, we sought out to learn a bit more about the natural history of willows. We hope you enjoy!

Humans and Willows

Human relationships with willow are diverse: including medicine (aspirin is derived from the active component salicin found in willow bark); furniture making (wicker furniture is made of willow), food (willow catkins are edible), and most notably, basketry.

But how far back have humans been weaving baskets with Willows? The archeological record of willow pack baskets dates far back to at least 900 BCE throughout the Americas, Asia, Africa and Europe – and for good reason. While a shallow basket is the best structure for carrying sensitive forage items like berries and mushrooms, heavier items like acorns or apples and wood or gear can also be accommodated in larger baskets. A sturdy willow pack basket allows both arms to be free to gather and explore!

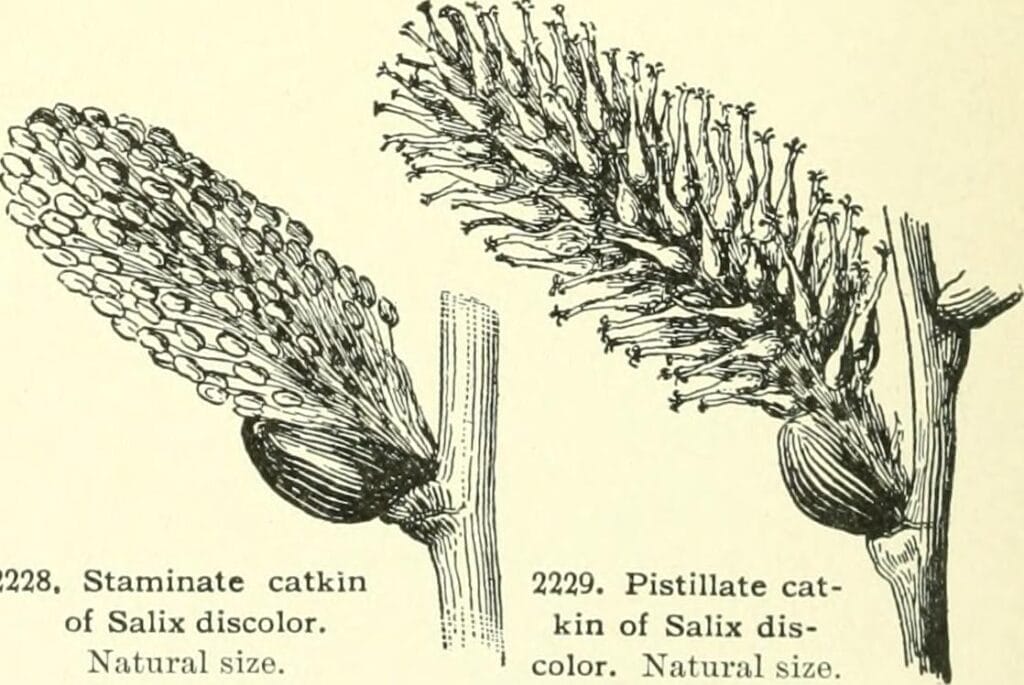

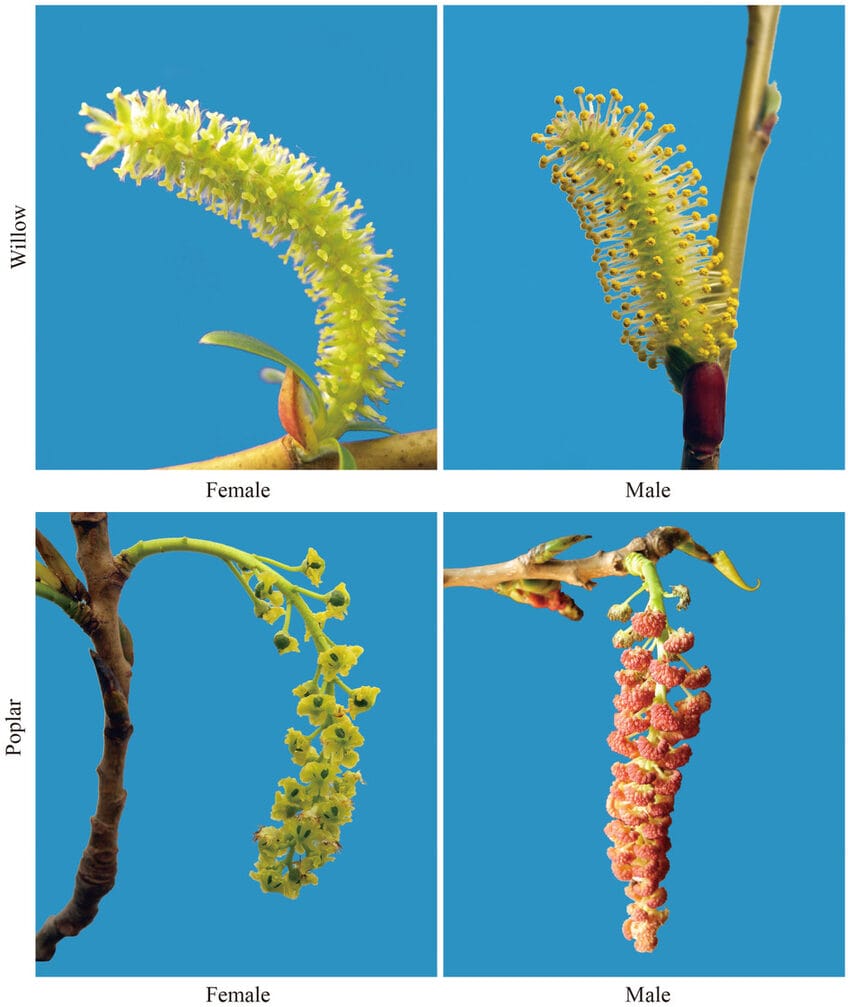

Pollinators of Willows

Willows are angiosperms, meaning their catkins are made of tiny flowers that co-evolved with insects! Many wild bees use willows as their primary food source. Since most species of willows are among the first plants to flower in spring, willows are an important source of nectar for pollinators during that sensitive time. Planting willows near your garden and orchard might be a way to mitigate hive collapse and declines in pollinator species.

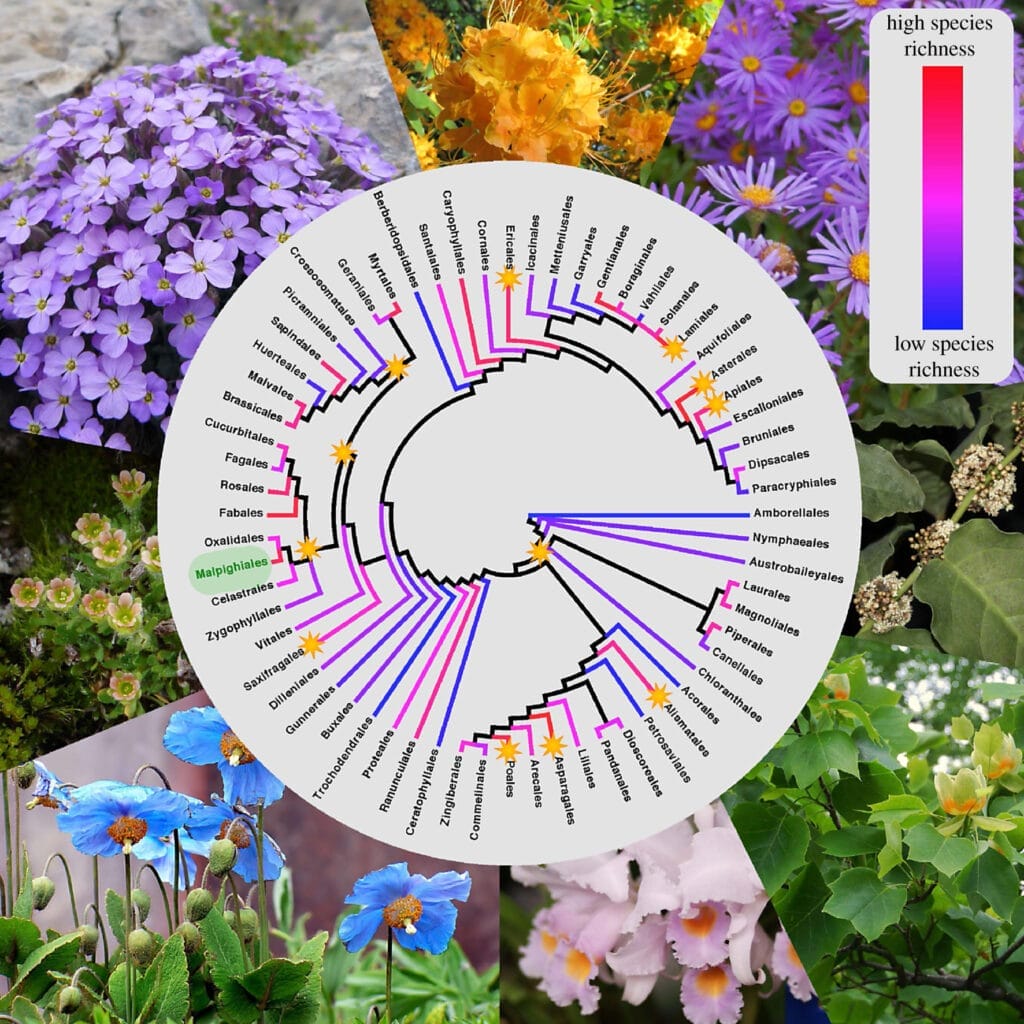

Who are their Close Relatives and When did Willows Evolve?

Willows belong to a plant family called the Salicaceae, along with their sisters: the Cottonwoods and Aspen. According to a really neat site that compiles genomic research about flowering plants and their co-evolved insect friends, the Salicaceae began diversifying about 80 million years ago – that’s just before the K-Pa Extinction which wiped out about three-quarters of all life on earth, including the dinosaurs. But the mighty Salicaceae family were able to persevere through that mass extinction and radiate out into the world, diversifying and evolving into the plant species we know today. Now that is flexibility!

Soil Ecology of Willows

Willows have a thriving rhizosphere, meaning they have a resilient community of mutualistic microbiota that live in a thin layer around its roots. This community includes various species of mycorrhizal partners that differ based upon locality. Since willows are an early succession plant, they help establish the microbial foundations for later succession forests.

What Willow species are native to the Southeast?

The southeastern US has about 12 species of native Willows, and 7 species of introduced and naturalized willows. In western North Carolina, the native Black Willow (Salix nigra) which usually forms tall trees, is the most common, followed by XXXX (Salix humilis var humilis) which usually forms small shrubs. Eurasian willows have naturalized in our area, including XXXX (Salix cericea) and Basket willow (Salix purpurea).. A monograph on Southeastern Willows by George Argus includes excellent keys to native and naturalized species. Many native species aren’t idea for basketry (e.g. large baskets require stalks to be non-branching), so many people cultivate Eurasian species with care and commitment to best practices so that native species can continue to thrive

As a community, lets intertwine our root masses of relationships so that soil and soul can stay in place, in the same way that willows prevent stream erosion. Lets collectively create flexible stems and skills that help us weave baskets of inclusivity and resilience. And may we cultivate adaptability so that we are able to re-root even if we’re torn away by the floodwaters and lost for some time

If you didn’t register in time for our Willow Pack Basket workshop with Tyler Lavenberg (waiting list only), there’s a good chance there’ll be a similar workshop at an upcoming Annual Gathering. In the meantime, we invite you to learn more about the Magnificent Trees with Luke Cannon on November 6!

We hope you’ll join us in weaving a future that’s resilient and inclusive, diverse and flexible, and fully alive.

About the author: Nastassja Noell is a lichenologist and Firefly Gathering’s Registration Coordinator. She loves weaving stories about ecological research and is a proud recipient of the United Plant Savers Deep Ecology Artists Fellowship. You can read more about her here.