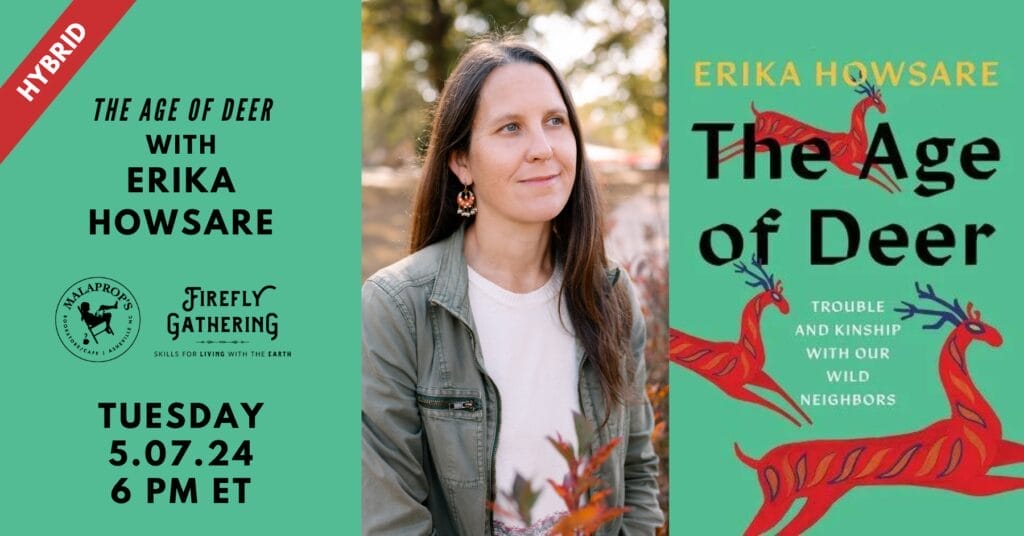

The Age of Deer Reading with Erika Howsare

This May, Firefly Gathering is excited to sponsor Erika Howsare’s reading of The Age of Deer at Malaprop’s Bookstore and Cafe. Erika’s masterful hybrid of nature writing and cultural studies investigates our connection with deer—from mythology to biology, from forests to cities, from coexistence to control and extermination—and invites readers to contemplate the paradoxes of how humans interact with and shape the natural world.

As a part of her studies, Erika shares the impact of her experience at the 2023 Annual Firefly Gathering, detailing her time in a bone crafting class with long-time instructor, Josh Barnwell. We hope you enjoy this first-hand account of Firefly Gathering in the excerpt below, and invite you to join us on Tuesday, May 7th at 6:00 pm for this event. Before you attend the reading, you can take an even deeper dive into Erika’s work with her companion podcast interview with Josh Barnwell here (episode: “CRAVING”)!

As a part of this exciting collaboration, any copies sold of The Age of Deer in April or May at Malaprop’s will donate a portion of the proceeds to Firefly Gathering. Order your copy from Malaprop’s here. Thanks for supporting local!

From Chapter 5, Kinfolk

Ever since I’d watched Mary Kate Claytor tanning that hide, the image of her stretching the deerskin over her bone awl had stayed with me. It wasn’t exactly that I kept seeing the action run like a film; more that I kept feeling the tool in my own hand. Then there was that list of 101 uses for a deer. It came from the Bulletin of Primitive Technology, not a scholarly journal but a manifestation of a strange and intriguing subculture that, like the awl, had lingered in the back of my mind.

And now here I was, sitting under a tent, feeling oddly surprised. I’d just looked down at my hand and found an awl that I myself had apparently made.

The tent was really just a piece of canvas stretched over rough wooden poles, and I sat beneath it with about eight other people. We were cross-legged on the ground in a ragged circle. For the last couple of hours, we’d been learning, from a man in buckskin shorts, how to make awls.

It was the first morning of my first-ever primitive skills gathering (also known in the movement as earthskills or ancestral skills). I’d traveled here, to the mountains of North Carolina, in order to spend nights camping in a field with hundreds of other people, and days taking classes on things that humans have been doing for millennia.

It was the most frankly countercultural scene I’d been in for a long time, a world in which fires were started by friction and my flashlight seemed out of place; everyone else found their way by moonlight. We started each day by gathering around a central fire pit, called there by blasts on a conch shell. We slept, sat, and ate on the ground. There wasn’t a cell phone in sight-phones didn’t work here, and anyway there was no place to plug them in. There were a lot of bare feet, a lot of buckskin, a lot of feathers in hats. The vibe was communal and joyful. If the gathering had a hedonistic edge, it mostly tended toward the wholesome: a little skinny-dipping here, some spontaneous ocarina playing there.

The talk around me was laced with mentions of native herbs and homesteading and rabbit snares. Once I overheard two people discussing supplies for very long road trips. One of them was about to travel out west, and the other seemed to live out of a car full-time. “What’s your diet?” asked the latter. “Do you eat meat or dairy?”

“No,” answered the first, “not unless I take part in the hunt- ing, skinning, or butchering, and it’s not often that that happens.”

“Do you want to help me skin a squirrel?”

As for the class list, deer were liberally sprinkled throughout, befitting their role as all-purpose preindustrial provider. These gatherings are a growing movement, with dozens every year around the U.S. and abroad, and for those who want to taste a hunter-gatherer mode of being, chances are good they’ll be dealing somehow with deer parts or their acquisition. My first stop was under this tent, in a bone awl workshop.

“Harder and sharper than wood, less brittle than stone, bone meets a material niche in ancestral skills and working with it helps us connect with the greater gifts of our animal kin,” the class description said. The session began with Josh Barnwell, the instructor, spilling out a pile of bones onto a canvas sheet on the ground. They were raw-looking, in shades of ecru and mauve, and each one was really a pair-the ulna and radius from a deer’s foreleg, fused by tough connective tissue.

Josh had some pretty intense visual aids for the anatomy part of the lesson: he picked up a deer’s hoof and several inches of furry lower leg connected to a naked white bone, then fit it together like a puzzle with the meaty top and shoulder of a different leg, this one blackened by fire. “Someone brought in a car-killed deer last night and we ate some of it for dinner,” he said matter-of-factly. He used a sharp knife to slice away the meat from the radius and ulna, the same bones we’d be working with. “That’ll be lunch.”

He was probably not yet forty, confident, warm, with a partially shaved head and a tree tattoo on his upper arm. “Find a bone that calls to you,” he told us, and each of us took one from the pile.

Our first step was to separate the two bones by cutting through the connective tissue. I soon settled into what I realized would be a long, repetitive task. At their ends, the bones fit together so tightly it was hard even to find the seam. Along their length, the narrow gap between them was entirely filled with sinew. I made tiny strokes with a craft knife into those steely fibers: dozens of strokes, hundreds of strokes, and once in a while a fragment came loose and I picked or peeled it away.

The work wasn’t tedious, though. It felt good; it was pleasure. As soon as I’d touched the bones I’d noticed that they felt slightly greasy, and while I worked my hands were picking up that oil, with its smell somewhere between leather and venison. The essential oil of what deer eat and are, a scent as unique as pine.

Josh told us these bones came from deer he’d picked up by the side of the road. He said he did this eight or ten times a year, providing food and materials for many kinds of projects. “Every year, I think, ‘This is the year I’m going to hunt,’” he said. “But I haven’t hunted yet because cars keep doing the killing for me.”

We scraped and scraped. Eventually one woman got to the next step: bone-sawing through the thinnest part of the ulna and then levering half of it up and away from the radius, with a meaty ripping sound. Everyone applauded, like she’d pulled the sword from the stone. I thought of Emily Dickinson’s line “And all our Sinew tore-” It’s from a poem of grief, the dismemberment of the heart. No accident that as we sat, most of us still working to separate one bone from another, we began talking about death. How our culture denies it. How, as life’s necessary partner, death is actually very sacred.

Here was the idea that was new to me, though: that shaping and using animal parts, making things that could support human life, might be a way to honor and accept death itself. Somewhere near Josh’s home, a deer had died a bad death, and now I was getting to know, quite intimately, part of its body, dismantling this structure in what might have been a form of atonement.

Finally, suddenly, the ulna came free. It was time to take up sandpaper and begin to shape the awl. Fairly quickly I sanded a slender, tapered point onto the end of the bone. The sandpaper was just regular old 80-grit from a hardware store, and someone asked what you could use if you wanted to avoid this modern product. Josh replied that you could take a piece of buckskin, get it wet, and then dip it in sand. “Bone is shaped more by abrading than by cutting or chipping,” he said.

He told us he’d been developing these skills since childhood, when he first got interested in edible wild plants, and attending gatherings since he was a teenager.

Listening to him describe a life that revolved around processing deer and making things from their parts, I asked myself what I used my own hands for, and the first thing that came to mind. was “typing.” It’s not often that I actually make an object, and I didn’t think I’d ever made a tool before.

Which is why it caught me off guard to look down, a while later, and find a finished awl in my hand.

I’d sharpened the point until it was pretty fearsome, and I’d spent a long time polishing the surfaces, removing all the sinew I could with knife, sandpaper, and thumbnail. But the best thing-the eerie thing-was how the handle end needed no shaping whatsoever. It was already a perfect fit for my hand. There was a flattish, wing-shaped butt end that rested in my palm, and the protrusions on the underside, where it had fused with the radius, made grips for each finger to wrap around. It was made by the deer-not for me, surely, though it was hard to ignore its precise correspondence to my own anatomy. To hold it was a bodily embrace.

I spent another couple of days at the gathering, sinking out of my usual sense of time, enjoying the anachronisms, and how I sometimes forgot which way they went. I made a pouch from rawhide that still had some fur on it, and I watched some women scraping deerskins over PVC beams. A four-year-old child chewed dreamily on some jerky, then fell asleep on a piece of buckskin dyed by acorns. Down the hill, there were several camper vans parked in a semicircle with antlers on their dashboards. In the tent where crafts were for sale, I looked at antler fridge magnets, expensive luxurious rolls of buckskin, buckskin anklets decorated with deer hoof rattles.

I had discovered another borderland occupied by deer. In this gathering, we were hovering somewhere between nostalgia and preparation. The movement had a complicated relationship with the past, as well as with Indigenous people of the present. Certainly there were Native people here, to teach and learn. And like many other organizations, the gathering was actively trying to correct for its overall whiteness. But what did it mean for a person like me, whose European ancestors had probably stopped making things from bone several thousand years ago, to fashion that awl? And were we here for enjoyment, or was it something more serious?

“These are skills that humans need,” my neighbor in the camping field told me in sober tones. “We don’t know what’s to come.” One class was taught by a man who said he’d foraged or grown 100 percent of his food for an entire year. Certainly, I thought, knowing how to hunt and process deer would put that kind of self-reliance within much closer reach.

It was another aspect of life among the ruins. For those who peer into the future-with climate crisis, social instability, and pandemics bearing down-and conclude that survival will mean going back to the land, a gathering like this might serve as a kind of boot camp. In this corner of our culture, just as for so many people through history, reliance on deer means a way to stay alive.

I kept thinking of something Josh had said near the end of his session. There had been a little contented silence while all of us were absorbed in sanding our awls, the dust of deer bones drifting down into the soil. “I always feel like it’s a such a human thing,” he’d said suddenly, “to be sitting in a circle, working on something.”

I went out to look for my younger daughter in the yard the other day, and found her digging a hole with a deer antler. Under the green plastic slide, wearing an old hockey T-shirt, she was scraping away at the ground with the antler’s biggest, sharpest point.

It was working very well to loosen the soil, though a little slower than a metal trowel would have been. She’d scrape for a while, then scoop out the dirt with a thick, broken clamshell we brought home from the beach this summer.

“Wow, you’re really doing it the hunter-gatherer way,” I said.

“Really?” she said. She hadn’t thought of that. It had just seemed right.

About the Author

Born and raised in southwestern Pennsylvania, Erika Howsare earned a BA at Oberlin College and holds an MFA from Brown University. She is the author of two books of poetry and her essays, reviews, and interviews are found at places like The Rumpus, The Los Angeles Review of Books, LongReads, and The Brooklyn Rail. Along with her husband and two daughters, Erika live in the Blue Ridge of central Virginia, where she works in local journalism and teaches writing in the community.

About Josh Barnwell

Josh Barnwell has been sharing his knowledge and passion for the outdoors from a young age. He teaches for private groups as well as at gatherings like Earthskills Rendezvous, Firefly Gathering, Florida Earthskills Gathering, and many summer camps. Read our interview with Josh, and follow him at Be Well Outdoors.

About Malaprops

Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café is an independent bookstore founded in Asheville, NC in 1982. We bring books, writers, and readers together in an environment that nurtures community and the joy of reading. We carry a carefully curated selection of books for adults, children, and young adults, as well as a large array of gift items. Our cozy café offers tasty treats from local bakeries and coffee roasted locally.